Where is The Voice of The Country.

︎ Social transitions

︎ Ecological transitions

︎ Spatial transitions

︎ Un-built environments

︎ Built environments

The landscape of Bangladesh has always been a changing landscape. Seasonal changes come not only with floodings, but with land submerging and extricating. With the on-going climate change, Bangladesh is facing a 50 cm rise of the sea-level, which translates to losing more than 11% of its land and affecting 15 million people. What are these landscapes telling us? If we listen.

Changing landscapes in Bangladesh

The landscape of Bangladesh has always been a changing landscape. The country is a delta with two-thirds of the country less than 5 metres above sea-level. It is also home to one of the largest mangrove forest in the world, the Sundarbans in the Bay of Bengal – a carbon sink crucial to the planet. Seasonal changes come not only with flooding, but with land submerging and extricating. With the on-going climate change, Bangladesh is facing a 50 cm rise of the sea-level, which translates to losing more than 11% of its land and affecting 15 million people. What are these landscapes telling us?

Landscapes are visible, multi-layered and complex systems. Landscapes hold resources, meaning and experience. They contain stories about who we are and who we were, what we have done and what actions and perspectives may be needed tomorrow. We need to interpret and understand landscapes through collective perceptions of where we live, on what land we live, perceived through our literary and visual culture.

“Our land is like a poem, in a patchwork landscape of other poems, written by hundreds of people, both those here now and the many hundreds that came before us, with each generation adding new layers of meaning and experience. And the poem, if you can read it, tells a complex truth. It has both moments of great beauty and of heartbreak.”

James Rebanks. English Pastoral. An Inheritance (2020)

The sea level defines much of the Bangladesh landscape and the challenges for mankind to create a living space in this country. With the on-going climate change, forecasting a 50 cm rise in the sea level, Bangladesh is looking at losing more than 11% of its land, affecting 15 million people.

A rise in the sea-level will also impact the world’s largest mangrove forest, the Sundarbans, which plays a planetary role in carbon sequestration.

The forecasted loss of land will in effect leave one in every seven people in Bangladesh displaced by climate change. With land already being a scarce resource, an estimated 6.5 million people live in the so called riverine islands, whereof 2 million are extremely poor.

These islands are constantly submerging and extricating in the delta and the newly emerged islands offer fertile soil, so despite the instability people have adapted their lives accordingly. They live in modular houses that can be assembled and disassembled within a day – and bought in the local market. In one of the more unstable rivers, Jamuna, people move on average up to 10 times in a lifetime.

With climate change causing increasing frequency and magnitude of floodings, the riverine people are at risk of losing both home and livelihood.

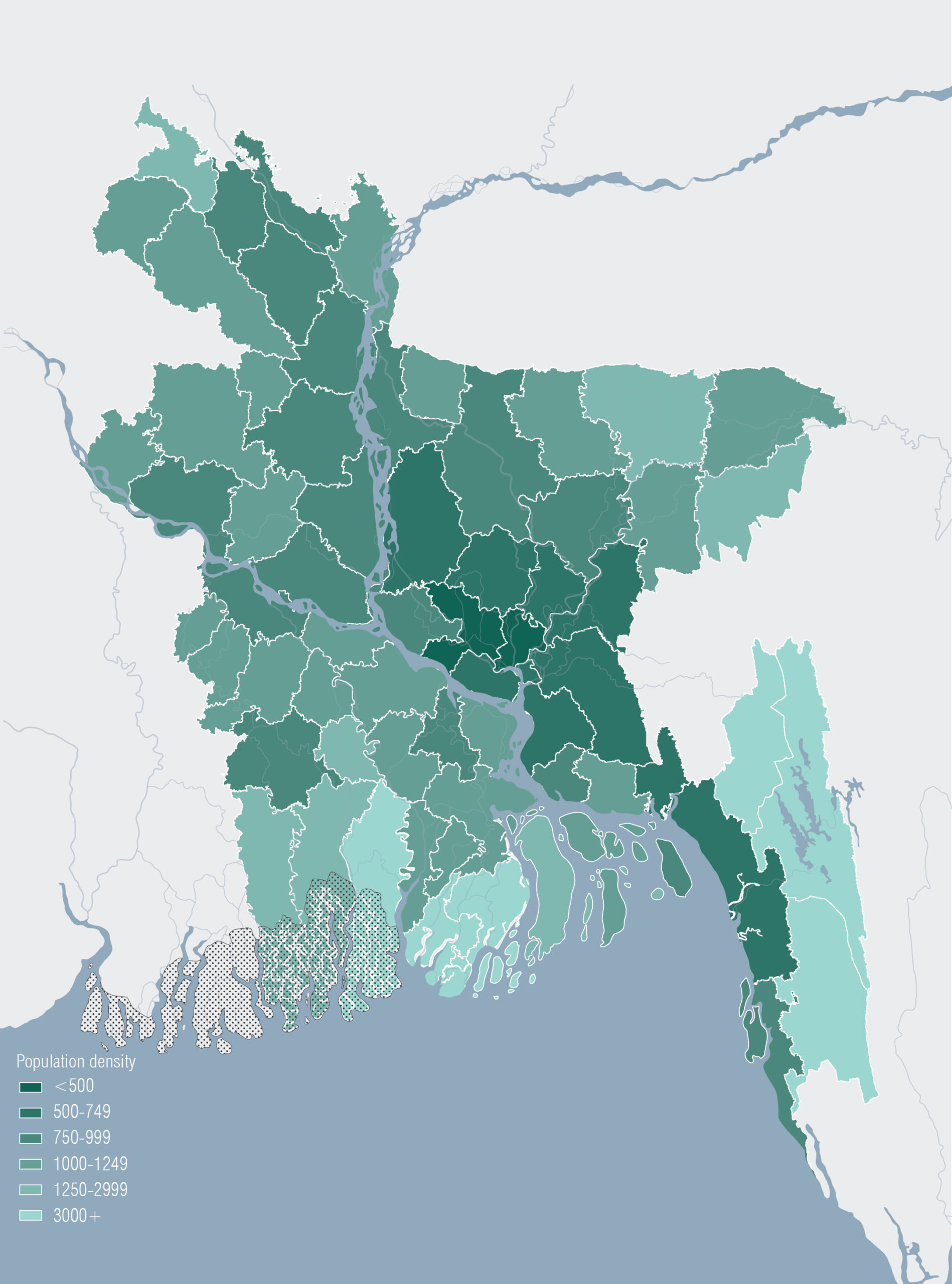

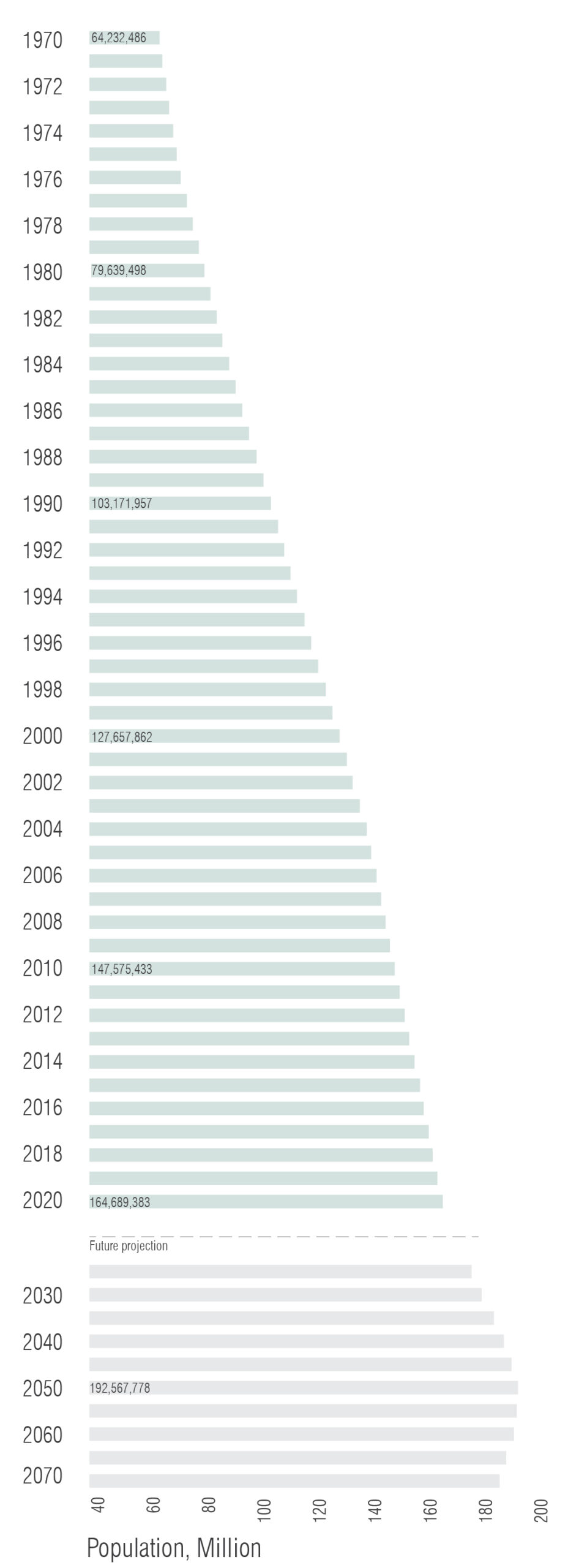

With an ever growing population, Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world. Close to 165 million people share 148,500 km2.

A density comparison shows Bangladesh with 1,265 people/km2; the Netherlands 508 people/km2 (the most densely populated country in Europe); and Sweden 25 people/km2.

The Bangladesh population is expected to continue to grow, with a forecasted peak around 2050 – during the same period of time 11% of its land is expected to disappear.

That is another 30 years with multiple generations facing even higher density, with less land and less resources. In the riverine islands, in Dhaka, in the Sundarbans – and beyond.

The European Landscape Convention (ELC) defines landscapes as “part of the land, as perceived by local people or visitors, which evolves through time as a result of being acted upon by natural forces and human beings.”

But landscapes are not only “acted upon” by human beings. Landscapes arepeople. The char dwellers living in the riverine islands are part of the riverine landscape. Just as the Munda people is part of the Sundarbans since some 300 years ago when they travelled here from India. Char dwellers and munda alike depend on the ecology and the landscape for their subsistence and livelihoods.

Anne Whiston Spirn, professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning at MIT, has been researching landscape literacy since the 80s. Spirn claims that “Individuals and societies inscribe their values, beliefs, ideas, and identity in the landscapes they create, leaving a legacy of stories told and read through a language of landscape with its own elements, pragmatics, and poetics” (Spirn 1998).

ELC also encourages us “to take an active part in its protection, conserving and maintaining the heritage value of a particular landscape, in its management, helping to steer changes brought about by economic, social or environmental necessity, and in its planning, particularly for those areas most radically affected by change, such as peri-urban, industrial and coastal areas.”

Translating the ELC definition into a Bangladesh context, ‘coastal areas’ provides a few perspectives on the situation significant for its landscape.

The ‘natural forces’ are implicit in defining the landscapes of Bangladesh. The riverine islands submerging and extricating in the delta. The mangrove forest as a protection from destruction of cyclones, coastal erosion and storm surges.

The result of landscape being acted upon by ‘human beings’ however, brings us into the energy landscape of Bangladesh. The on-going climate change, caused by CO2 emissions, which in turned is caused by ‘human beings’, is forecasted to cause a significant rise in the sea level. This will affect 15 million people, at risk of becoming climate migrants, and the carbon sink Sundarbans, losing substantial amounts of blue carbon – as a consequence causing domino effects.

Mangroves are natural carbon sinks as they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in its biomass. Located in the Bay of Bengal, the Sundarbans absorbs more than 40 million tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Its 140,000 ha contains a critical ecosystem with diversified species which composition of high salient tolerant (saltwater) species and freshwater species is put out of balance by a rise in sea level and leading to substantial loss of blue carbon.

For the people in this country, the mangrove forest functions as a protection from destruction of cyclones, coastal erosion, floodings and storm surges. For the same reason the Sundarbans is an area of great concern also to the neighbouring country India, harbouring approximately 40% of the mangrove forest.

It is also home to 4.5 million people, dependent on the mangrove for their livelihood. Hence, speaking with Rebanks, the Sundarbans contains layers of human meaning and experience, if we listen.

Since 1997, the Sundarbans mangrove forest is a UNESCO world heritage, defined as “the largest contiguous mangrove forest in the world” with “an outstanding universal value”.

In other words, the Sundarbans is a planetary concern.

The past 20 years or so, Bangladesh GDP has been increasing steadily and is projected to increase even more in the coming years. Even though the majority of the population is engaged in the agricultural sector (40.6%), GDP contribution is small. Instead, it is the growing service sector that contributes the most.

The overall GDP growth is reflected in the total energy consumption. However, not in the consumption pattern. While industries such as mining, electricity and gas construction consume 60% of the total energy, this is not reflected in its contribution to the country’s GDP, which is less than half of that from the service sector. Here, cheap labour is part of reading this landscape.

As people come at a low price in Bangladesh, some areas are left with as many as close to 70% of the population poor. The Brahmaputra floodplain in the north, the tidal delta in the south, and the hill tracts in the south-western part of the country are among the poorest.

This tells us that some of the poorest and most densely populated areas in this country are the same as those facing a 50 cm rise of the sea level over the next decades.

This tells us that some of the poorest and most densely populated areas in this country are the same as those facing a 50 cm rise of the sea level over the next decades.

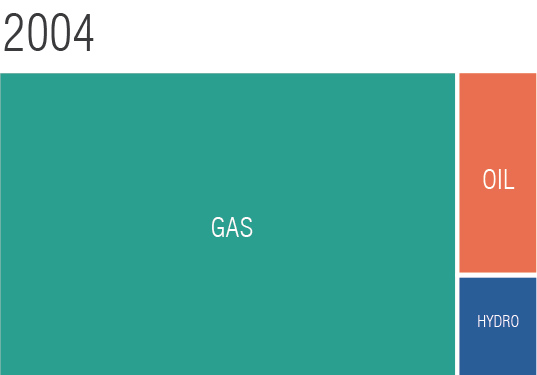

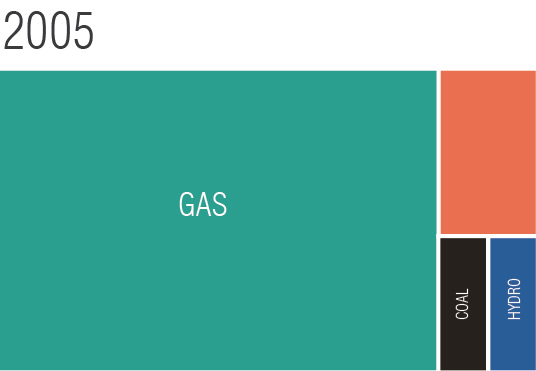

Until 2005, coal was a non-existing energy source in Bangladesh. The first coal-based power plant was built in 2006. For comparison, Europe entered its coal-driven journey some 115 years earlier, with the first coal-fired public power station built in London in 1890.

So, why coal and why now?

Bangladesh has been relying on its domestic natural gas, a resource that peaked in 2018 and now deteriorating. Therefore, infrastructure and investments are since some 15 years back put into supplying Bangladesh with imported coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG). With the existing 149 power plants, where more than half relies on natural gas for its electricity production, there is a huge gap between national energy production and primary energy use.

With a strong demand for more and cheap energy in order to maintain the industry and continue to increase GDP in Bangladesh, the major share of electricity will be used mainly by industries, new investments in energy production are necessary.

A growing GDP is one measure to decrease poverty or at least keep it at bay.

More energy is also necessary if Bangladesh is going to meet the global demand for the garments it manufactures, which makes up 91.5% of the country’s exports.

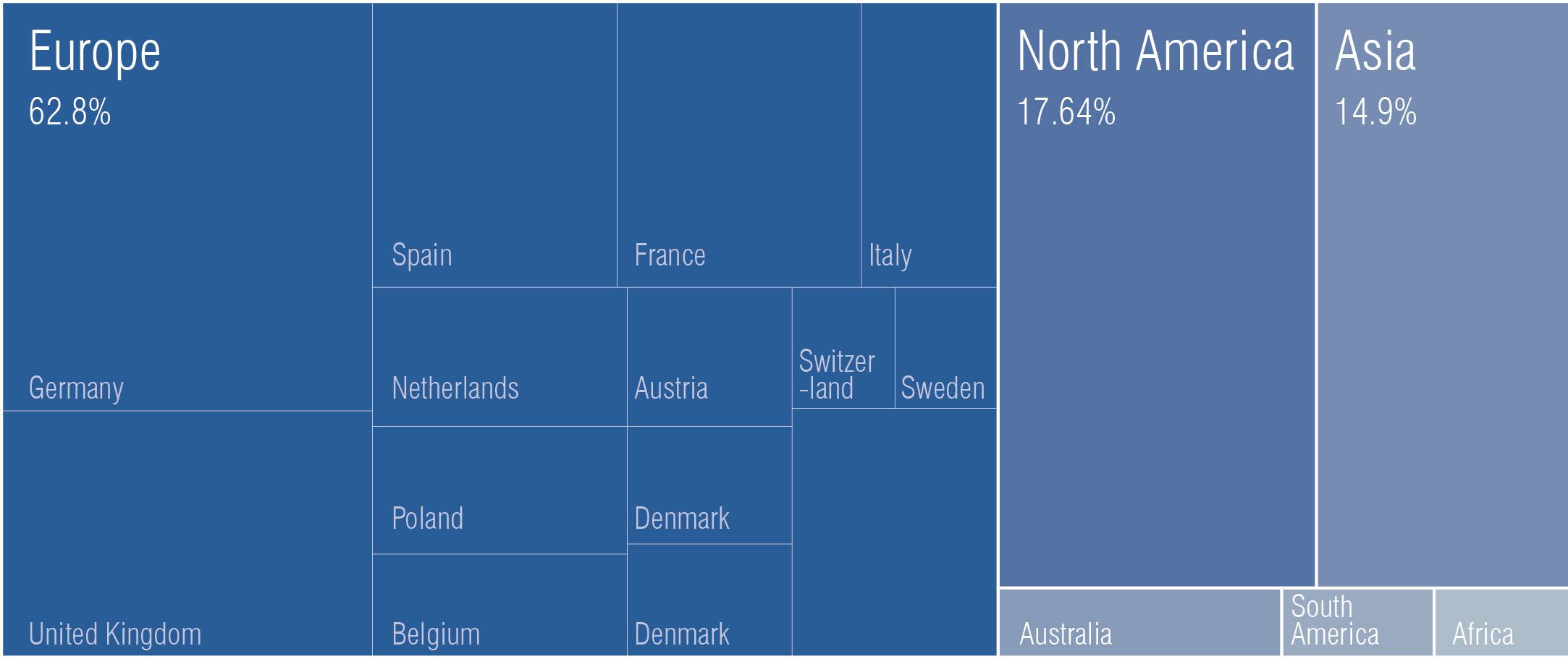

Demand is primarily coming from Europe being by far the largest export market making up 62.8% of Bangladesh total exports, followed way behind by North America with some 17.6%.

To meet global demand and speed up expansion of installed capacity, Bangladesh has issued policies that render private companies the opportunity to now invest and generate electricity without paying income tax for 15 years. And, investors can use any energy source.

During the same time span as Europe is taking measures to reduce its dependence on coal, Bangladesh is thus moving in the opposite direction, increasing its use of coal. And this mainly to safeguard energy capacity for the manufacturing industry supplying markets in Europe. This is an answer to global demands, including European consumer markets.

At this point, when Europe is taking measures to reduce its dependence on coal and Bangladesh is moving in the opposite direction, we need to remember that coal has been deeply connected with European industrialization, development, and pride. Ever since the world’s first coal-fired public power station was built in London in 1890 (the Edison Electric Light Station, a project of Thomas Edison organized by Edward Johnson), coal has been a pivotal economical building block of European society.

Government has taken up a number of initiatives to promote the use of renewable energy. This year (2021) the total renewable energy capacity reached some 776 MW, of which 70% was solar energy. Solar energy is the most adequate renewable energy source in Bangladesh. Thus, the Government has initiated 500 MW solar programs, Solar Home System (SHS), solar mini-grid, solar rooftop, solar irrigation, etc..

However, despite the policies granting tax exemption, the country has failed to attract investments and is still nowhere near its target of generating renewable.

Proportions of total energy production in Bangladesh. Installed capacity: non renewable versus renewable energy (2021).

Total renewable energy. Installed capacity: 776.13 MW (2021), whereof solar 542.13 MW and wind 2.9 MW.

Several of these plants are proposed to be located in coastal areas (look to the ELC definition that summons to take ‘active part in its protection, conserving and maintaining the heritage value of a particular landscape, in its management, helping to steer changes brought about by economic, social or environmental necessity, and in its planning, particularly for those areas most radically affected by change, such as…‘coastal areas’). One of the proposed coal power plants is the Rampal power station, a 50/50 joint venture with India, placed within a radius of 14 kilometers north of the Sundarbans – ‘a sensitive area’ reading the ELC, and a voice of the country.

Since Sundarban concerns India as well, about 40% of the mangrove forest lies in the country, the Ministry of Environment and Forests of India (EIA) states that no thermal power plant is allowed within 25 km of an ecologically sensitive area, natural forest or wildlife habitats. Now, the Rampal power station would be placed in Bangladesh, and of course outside Indian jurisdiction, yet the Sundarbans neither knows nor adheres to any state borders.

Landscapes have their own expressive aesthetic, natural, cultural, and exploitable qualities – all of them perceived and valued in multiple ways. In the case of Bangladesh it seems the exploitable qualities continue to be predominant.

Landscapes are sensitive, ecologically and culturally, to changes on local and regional levels through global scales. Bangladesh is no exception. Yet, construction, destruction, and re-invention of the landscapes all repeat themselves without acknowledging that the most vulnerable people are also the most vulnerable landscapes; without acknowledging the risk of increasing CO2 emissions on the edge of a planetary carbon sink; without acknowledging that the energy production and consumption that affect landscapes are not the major contributor to the GDP.

If we are to understand place specific landscapes, we need to understand whatthese landscapes are, what they are about, what they tell us. In the specific place of the Sundarbans, UNESCO yields to that, “it is a landmark of ancient heritage of mythological and historical events”.

So, what can the Sundarbans, the riverine islands and its people tell us? What can the Brahmaputra floodplain and the hill tracts tell us? If we listen.

Landscape literacy is about understanding how landscapes emerge, by what means they are sustained, what we do and how we relate to them, emotionally, socially and economically. And how we communicate with and through these landscapes.

As Rebanks writes, the landscape is like a poem, and if we can read it, it will share with us complex truths that we need to understand and reconnect with in order to find a sustainable path forward. Are we prepared to hear the stories told and read through a language of landscape with its own elements, to speak with Spirn?

Are we prepared then, to give this country a voice?

LABLAB

ROSENLUNDSGATAN 38

118 53 STOCKHOLM