Curated and Catered.

︎︎There are three kettles in hell. The first is heavily guarded. Here the Finns boil. If one tries to escape, the others attempt to help them. The second kettle is poorly guarded. Here the Russians boil. If one tries to escape, the others watch them. The third kettle is unguarded. Here Estonians boil. If one tries to escape, the others pull them back. — Estonian anecdote

By Mattias Malk

As a researcher of the urban, I have a particular lens on the city. Sometimes the lens is literal—I make photographs and study archival images. Often the lens is critical, requiring time and distance to unpack the subject. But as much as any lens offers the chance to focus, it also implies a frame from which omissions must be made. As my focus is so often on the city, this omission tends to be the so-called “countryside”. At the same time I am aware it is self-evident how the city can not exist without the countryside. Aspects of each exist in both. AsKeiti Kljavin put it in another LABLAB essay: the urban and the rural are mutually constitutive. Moreover, arguing for or against a shift from one to another is near defunct. It is, however, interesting and understudied, to what end this distinction is maintained. I welcome the invitation to particularly consider the countryside and its role in an increasingly urban world.

︎︎︎It has been said that one of the best ways to take stock of social change is to look at developments in housing. I propose to do so by examining the shifting form of the most iconic feature of the Estonian countryside I know: the barn-dwelling rehielamu. The study takes the form of a triad composed of this text and two visual collages: one of archival images and one of material collected from Instagram tags. The three together form an attempt to triangulate farm form, and situate its relevance in staging the countryside in a society of cities.

︎︎︎First briefly about Estonia. Here the countryside is deeply rooted in constructing the national identity. For Estonians the forest, the sea and the land are anchors for a stable self as much as language, culture and digital enterprise. The most architectural articulation of staging this relationship with the countryside is the barn-dwelling. This essay briefly considers how the countryside is and has been staged by forefronting the changing form of the barn-dwelling.

For about a millennium the house of an Estonian remained unchanged. Described as simple, close to nature, traditional and unchanging it mirrored its inhabitants. Life was largely communal and dictated by seasonal work. The farm was organised around a central yard which framed and facilitated the household. At the time the concept of a family did not consist solely of blood relatives, but extended to the entire economic unit housed under one roof. Much of life spilled out onto the street and was intensely public. Events of importance such as weddings or funerals were always celebrated with the entire community of the village and only a true stranger would ever knock before entering a household.

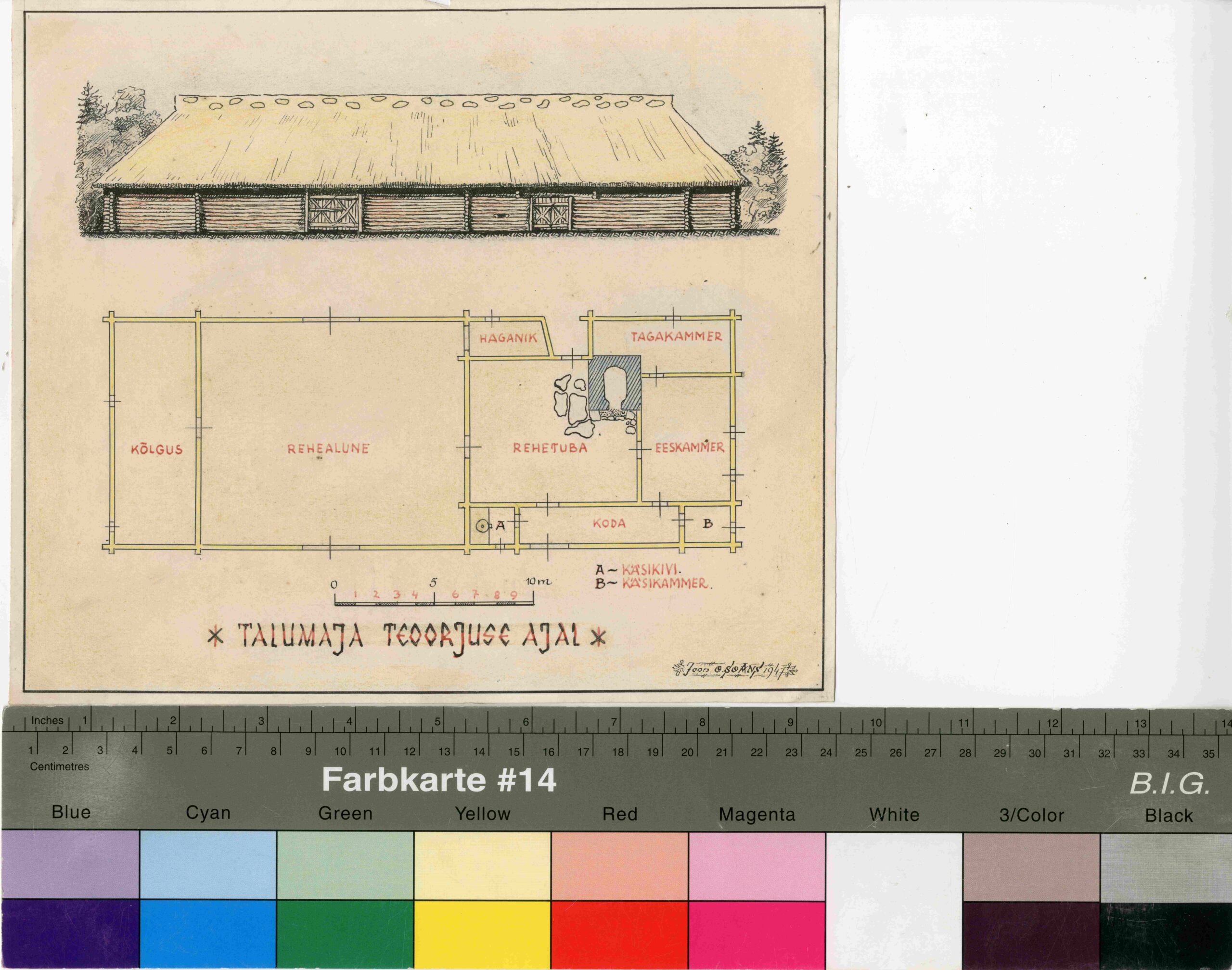

︎︎︎The most important structure on the farm was the barn-dwelling. Historically unique in connecting housing with husbandry, its simple combined structure was a response to the cool climate and abundant precipitation, allowing for drying and threshing grain as well as housing animals over winter. As a human dwelling it had several disadvantages though, being dark, low and without a chimney. The whole family would share one heated open multipurpose space, which in truth was semi-public. Its walls did separate the family from the outside, but inside there were no partitions, no “personal space”. In a sense, a person was not considered an individual, but rather a member of the family, which functioned as an economic unit.

︎︎︎These primitive and often unsanitary conditions were unpalatable to the enlightened humanists and land owners of the 18. and 19. century, who made several attempts to improve local housing conditions. The local peasants were slow to give up their traditional ways. However, from the mid-19th century onward, the farmhouse underwent rapid and fundamental change alongside its inhabitants.

︎︎︎Fundamental shifts in the countryside occurred with the arrival of capitalism in the second half of the 19th century. Farms could now be bought and sold, serfdom was abolished. Land was redistributed and the small plots peasants were so far allotted were combined into larger holdings. This had a fundamental impact on how public life was organised in villages, but also resulted in changing housing conditions. With the available social and economic means traditional barn-dwellings were no longer renovated. Instead the capital-empowered countryside became filled with modernised housing, which enabled an entirely different way of life.

![]()

Mid-war independence, Soviet occupation and reprivatisation all left their mark on the barn-dwelling. Its form and formula has now shifted from thresh to tourists.Since the 1990s, accommodating, catering and creating recreational experiences for visitors has set an example for an alternative to fickle income from agriculture. More and more farmers now see the tourist as the most reliable harvest.

︎︎︎In adopting the most suitable conditions for the newly found crop, the farm has been adjusting into a new form. Being synonymous for the kind of “authentic experience” sought by the visitors, the barn-dwelling and its courtyard still set the stage for the countryside. The interior and exterior of the farmhouse, however, are radically transformed to cater for comfortable dwelling. Modern amenities are added, rooms are restructured and often the barn portion is demolished completely. The courtyard becomes a simulacrum of itself—here the act of rurality is performed and participated in.

The contemporary tourism farm invites local and international urbanites alike to briefly become rural. It offers pastoral “authenticity” craved by citydwellers without the grit and grime of agriculture. Only a short drive from whatever arbitrary reference point, the countryside is here neatly curated and punctually catered. Here one can feel a connection without having to sacrifice their urbanite individualism. Get a hot sauna, full stomach and good rest without having to do the work. Or if one prefers, they can indeed pay to undertake agricultural labour.

![]()

The countryside, land and agriculture forged the foundation for an Estonian way of life. For some time this way of life departed from the barn-dwelling. First enticed by the Baltic Germans, then forced by the Soviets, Estonians and their houses have changed significantly in the past two centuries. The form of the farmhouse has been extensively researched up until the effects of Soviet collectivisation. In comparison, the architectural changes since the ownership reform in the 1990s, when land was returned to its pre-war owners, have been entirely understudied. This is in part because of a significant shift towards urbanisation, with life increasingly centred around Tallinn, and the overall breadth of changes which have occurred in Estonian society in general since becoming re-independent three decades ago.

︎︎︎Of the remaining 100 000 rural households, less and less are engaged in traditional agriculture. As purchasing power increases, many households are modernised and useless side structures demolished. Often historical buildings are moved to a new location or dismantled for their materials. It is clear that the traditional farmsteads which survive, are the ones which continue to be adapted and find use as housing or increasingly in farming agricultural tourists. Studying these shifting uses offers a valuable insight into the overall conditions and opportunities governing both rural and urban life in the region. Whereas the economies and politics, infrastructure and architecture of cities and their hinterlands are thoroughly intertwined, it is clear that the highly managed countryside plays a crucial supporting role for the modern urbanite. Though he no longer lives in the rehielamu, aspects of its form are still crucial to constituting the identity of the contemporary Estonian. These aspects, though, are highly curated.

︎︎︎It would now be near impossible to imagine Estonians as collectivistic. Spoiled by communism and liberalism alike, individuality and segregation are the new norm. Comfort, individuality and the aversion to cooperation have become the key reasons for stagnating quality of life. While the perceived form of the barn-dwelling remains one ideal housing typology, its inhabitants would now be happiest without another household within sight. Perhaps reframing collective endeavour based on the history of the barn-dwelling, rather than forced five year plans, has potential for the urban and the rural . If not for increased unity, then for decreased segregation. For now, let us at least make fun of ourselves.

Mattias Malk is a photographer and a PhD researcher at the Estonian Academy of Arts, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning.

︎︎︎The most important structure on the farm was the barn-dwelling. Historically unique in connecting housing with husbandry, its simple combined structure was a response to the cool climate and abundant precipitation, allowing for drying and threshing grain as well as housing animals over winter. As a human dwelling it had several disadvantages though, being dark, low and without a chimney. The whole family would share one heated open multipurpose space, which in truth was semi-public. Its walls did separate the family from the outside, but inside there were no partitions, no “personal space”. In a sense, a person was not considered an individual, but rather a member of the family, which functioned as an economic unit.

︎︎︎These primitive and often unsanitary conditions were unpalatable to the enlightened humanists and land owners of the 18. and 19. century, who made several attempts to improve local housing conditions. The local peasants were slow to give up their traditional ways. However, from the mid-19th century onward, the farmhouse underwent rapid and fundamental change alongside its inhabitants.

︎︎︎Fundamental shifts in the countryside occurred with the arrival of capitalism in the second half of the 19th century. Farms could now be bought and sold, serfdom was abolished. Land was redistributed and the small plots peasants were so far allotted were combined into larger holdings. This had a fundamental impact on how public life was organised in villages, but also resulted in changing housing conditions. With the available social and economic means traditional barn-dwellings were no longer renovated. Instead the capital-empowered countryside became filled with modernised housing, which enabled an entirely different way of life.

Mid-war independence, Soviet occupation and reprivatisation all left their mark on the barn-dwelling. Its form and formula has now shifted from thresh to tourists.Since the 1990s, accommodating, catering and creating recreational experiences for visitors has set an example for an alternative to fickle income from agriculture. More and more farmers now see the tourist as the most reliable harvest.

︎︎︎In adopting the most suitable conditions for the newly found crop, the farm has been adjusting into a new form. Being synonymous for the kind of “authentic experience” sought by the visitors, the barn-dwelling and its courtyard still set the stage for the countryside. The interior and exterior of the farmhouse, however, are radically transformed to cater for comfortable dwelling. Modern amenities are added, rooms are restructured and often the barn portion is demolished completely. The courtyard becomes a simulacrum of itself—here the act of rurality is performed and participated in.

The contemporary tourism farm invites local and international urbanites alike to briefly become rural. It offers pastoral “authenticity” craved by citydwellers without the grit and grime of agriculture. Only a short drive from whatever arbitrary reference point, the countryside is here neatly curated and punctually catered. Here one can feel a connection without having to sacrifice their urbanite individualism. Get a hot sauna, full stomach and good rest without having to do the work. Or if one prefers, they can indeed pay to undertake agricultural labour.

The countryside, land and agriculture forged the foundation for an Estonian way of life. For some time this way of life departed from the barn-dwelling. First enticed by the Baltic Germans, then forced by the Soviets, Estonians and their houses have changed significantly in the past two centuries. The form of the farmhouse has been extensively researched up until the effects of Soviet collectivisation. In comparison, the architectural changes since the ownership reform in the 1990s, when land was returned to its pre-war owners, have been entirely understudied. This is in part because of a significant shift towards urbanisation, with life increasingly centred around Tallinn, and the overall breadth of changes which have occurred in Estonian society in general since becoming re-independent three decades ago.

︎︎︎Of the remaining 100 000 rural households, less and less are engaged in traditional agriculture. As purchasing power increases, many households are modernised and useless side structures demolished. Often historical buildings are moved to a new location or dismantled for their materials. It is clear that the traditional farmsteads which survive, are the ones which continue to be adapted and find use as housing or increasingly in farming agricultural tourists. Studying these shifting uses offers a valuable insight into the overall conditions and opportunities governing both rural and urban life in the region. Whereas the economies and politics, infrastructure and architecture of cities and their hinterlands are thoroughly intertwined, it is clear that the highly managed countryside plays a crucial supporting role for the modern urbanite. Though he no longer lives in the rehielamu, aspects of its form are still crucial to constituting the identity of the contemporary Estonian. These aspects, though, are highly curated.

︎︎︎It would now be near impossible to imagine Estonians as collectivistic. Spoiled by communism and liberalism alike, individuality and segregation are the new norm. Comfort, individuality and the aversion to cooperation have become the key reasons for stagnating quality of life. While the perceived form of the barn-dwelling remains one ideal housing typology, its inhabitants would now be happiest without another household within sight. Perhaps reframing collective endeavour based on the history of the barn-dwelling, rather than forced five year plans, has potential for the urban and the rural . If not for increased unity, then for decreased segregation. For now, let us at least make fun of ourselves.

Mattias Malk is a photographer and a PhD researcher at the Estonian Academy of Arts, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning.

LABLAB

ROSENLUNDSGATAN 38

118 53 STOCKHOLM